NATIONAL POPULAR VOTE

In America's outdated, unnecessarily undemocratic current Electoral College system, the artificially divisive red/blue paradigm excludes most states and voters from presidential campaigns.

An ingenious plan could re-engage them by making every state purple, every vote equal and the winner of the national popular vote President - without a Constitutional amendment.

These candidates for elector are men and women who promise that, if ultimately directed by their state (or District in the case of D.C), they will represent the state or District in the Electoral College to vote for the particular presidential and vice-presidential candidates to whom they are pledged. The Electoral College consists of all of the electors chosen throughout the country during that election and they meet, in their respective states (and the District), on a particular day in December to cast the actual votes that determine the President and Vice-President.

Each state or District is represented in the Electoral College by the same number of electors as it has representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate combined (with the District of Columbia, according to the Twenty-Third amendment to the U.S. Constitution, having the number of electors matching what its total representation would be if it were a state, so long as no actual state has less electors than the District). So, for example, as of the 2008 U.S. presidential election, California had 53 U.S. Representatives and 2 U.S. Senators. Therefore, it had 55 electoral votes. Similarly, Pennsylvania, which had 19 U.S. Representatives and 2 U.S. Senators, therefore had 21 electoral votes.

Thus, the total current size of the Electoral College is 538 electors, matching the total of the number of members of the U.S. House of Representatives (435) plus the number of U.S. Senators (100) plus 3 electors representing the District of Columbia.

Currently, as an American voter, when you vote in a presidential election, you are actually not directly voting for the candidate you support. Rather, you are voting for which group of electors you wish to have represent your state (or District) in the Electoral College. After you and your fellow citizens vote, each state or District then decides, based on the vote among its residents, and according to its particular election laws, which combination of electors has been chosen to represent the state in the Electoral College weeks later to actually vote for the candidates to whom they are pledged.

As of this writing in 2010, with only two exceptions, every state’s (and D.C.’s) laws mandate that its electors be chosen according to a winner-take-all system. In other words, if a candidate receives the most votes in that state or District, then that state or District’s full representation in the Electoral College will consist of electors pledged to that candidate.

It is the candidates that receive a majority of votes in the Electoral College – at least 270 out of the total 538 electoral votes - that ultimately become President and Vice-President.

The Problems with the Current Electoral College System

A candidate can lose the popular vote but still win the presidency

Within the current system, a candidate can lose the popular vote, but still win the Electoral College. In other words, he or she can become President even though he or she did not win the most votes among the public. In fact, not only can this happen, but it has happened several times.For example:

- In 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes won the presidency by one electoral vote, despite having lost the popular vote by over 250,000 votes. Hayes’ opponent, Samuel Tilden, actually received 51% of the popular vote to Hayes’ 48%.

- In 1888, Benjamin Harrison won the presidency by a wide margin in the Electoral College, despite losing the popular vote.

- In 2000, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore in the Electoral College, winning the presidency despite losing the popular vote by over 500,000 votes.

The ultimate result is that the current system allows for a President that was not chosen by the most voters in the country.

It literally makes a vote in a less populous state worth more than one in a more populous state

Despite that most treasured democratic ideal of every vote being equal, currently in U.S. presidential elections, they really aren’t. The worth of your vote depends on which state you vote in – specifically on its population. The smaller your state’s population, the more your vote is worth.For example, if you vote for President as a resident of Wyoming, your vote is worth more than if you vote as a resident of California. Why?

As the New York Times explains in a 2008 editorial:

“Wyoming’s roughly 500,000 people get three electoral votes. California, which has about 70 times Wyoming’s population, gets only 55 electoral votes.”Mathematically this means that each Wyoming resident represents a larger fraction of an electoral vote than does each resident of California. In other words, it takes far fewer voters in Wyoming to give the same relative amount of electoral support to a candidate as in California.

This is ultimately a consequence of basing the electoral power of a state on the combination of its number of U.S. Representatives and U.S. Senators. The U.S. Constitution gives every state, regardless of population, two U.S. Senators. Our founders set up the Senate this way to ensure that, at a time of great concern over the balance of state and federal power, more populous states didn’t completely override the desires of less populous ones in Congress. However, the Electoral College translates this purposeful imbalance in the Congress to a completely different area, the election of the President.

It incentivizes a nearly exclusive campaign focus on a small set of “swing states”

In the current system, presidential candidates know that, strategically, with almost no exceptions, they receive no benefit at all from winning even millions of votes in a given state if they don’t end up with the most votes in that state. Even if they receive great support in that state, and only narrowly lose it to another candidate, in terms of the Electoral College results, they may as well have spent no time there at all. Given these circumstances, wise presidential candidates are almost forced, even before their campaigns begin, to divide states into three categories:- Safe wins - States that consistently can be taken for granted as supportive of their party

- Predictable losses – States that consistently can be taken for granted as supportive of their opponent’s party

- Swing states – States that are close enough in support of each party to be influenced in one direction or the other through campaigning

This is why, in every presidential election cycle, a few swing states like Ohio and Florida receive constant attention, interest, advertising and campaign visits, while even large populous states like New York, Texas and California, with many millions of voters, receive hardly any at all.

In fact, according to FairVote:

“More than 98% of campaign spending and advertisements in the 2008 general election were in states representing barely a third of the country's population.”Also according to FairVote:

“From September 24 – two days before the first general election debate – through Election Day on November 4, 99.75% of all advertising spending was in just 18 states…. The remaining 32 states and the District of Columbia that received a combined 0.25% of campaign advertising were left as net exporters, sometimes in massive sums, of campaign money.”This means that many millions of people in non-swing states, even many who are donating to the presidential campaigns, are basically left out of the political campaign process itself. This situation is bad for any voter in a non-swing state. Regardless of whether a particular voter in such a state supports the winning or losing candidate, he or she misses out on the chance to really be invested in the campaign. This is why a friend of mine who lives in New York State recently mentioned to me how out of the loop of presidential campaigns he is.

I myself experienced the consequences of this situation very directly during the 2008 presidential campaign. I was very interested in that campaign and really enjoying the process as it played out in my home state of Michigan. Throughout the campaign, both major candidates were invested in winning the state and were visiting here periodically and addressing the issues important to the state. John McCain was scheduled to visit the state again the next week, when, on October 2, he decided to cancel that visit and give up on the state. Polls had led him to believe he couldn’t win the most votes in the state, and therefore, due to the current Electoral College system, he had no incentive to put in the energy or resources to try to win any. As the New York Times put it, his campaign decided to “redirect its resources to other swing states where they felt Mr. McCain had a better chance.”

With McCain having ceded Michigan, his opponent, Barack Obama, could put the state in his “safe win” column and pull many of his resources out of the state, as well. And just like that, a state of nearly 10 million people, whose issues were so central to the country’s concerns at that time, was practically off the radar of the major presidential campaigns. Regardless of which candidate I or anyone else in Michigan personally preferred to win the state, we were all effectively robbed of either campaign’s focus on our state from that point on.

If the system isn’t changed, most Americans in most states can look forward to more of what Michigan experienced in 2008 – the same lack of campaign attention that so many other non-swing states have experienced time and again in presidential elections.

As Saul Anuzis, former chairman for the Michigan Republican Party and Rhett Ruggerio, former National Committeeman from the Delaware Democratic Party, explain in an editorial:

“As Americans look forward to the next presidential election, the political reality of the race will be that the voters in at least 35 states will not matter. As in previous presidential elections, candidates will spend two thirds of their time and money in just six closely divided battleground states. Ninety-eight percent of their resources will be spent in only 15 states.”

This focus on swing states may lower voter turnout in the far more numerous and populous non-swing states

Within the current Electoral College system, voter turnout in non-swing states may be lower than it would otherwise be for at least two reasons:- As mentioned, presidential candidates generally avoid visiting, advertising or speaking to the issues important in non-swing states. Thus, voters there may simply not be as aware of or invested in the campaigns.

- Non-swing state voters that understand the current election system or follow politics may be aware that their state’s outcome can already be easily predicted. They also may hear constantly in the news that the election will depend only on the vote in the few swing states and notice the absence of discussion of their own state.

The focus on swing states may disproportionately favor certain groups of voters over others

Different racial, ethnic, religious and other groups are spread inconsistently throughout the various states of the United States. Some groups are more prevalent in some states than in others. Therefore, one other detrimental side effect of the focus on swing states is that it may lead, even if only as an accident of demographics, to presidential campaigns focusing more or less on particular groups of people based simply on whether they happen to be more or less concentrated in swing states.Separating the map into “red” and “blue” states exaggerates and escalates the perception of division between states

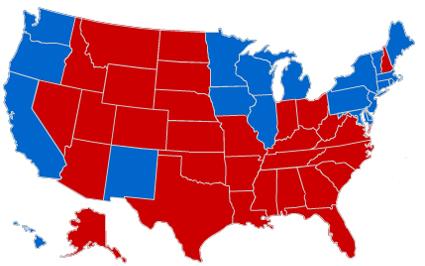

As mentioned, we can quite safely predict which party most of the states in the country will favor in any presidential election. Those that consistently favor Republicans are labeled as “red” states and those that consistently favor Democrats are labeled as “blue” states. Most of us, around election time, have seen the familiar red/blue state map (shown here from the 2000 presidential election).

The problem with this map is that, while it may accurately reflect the electoral results in the current system, it does not accurately reflect the true distribution of voters in the country in all its complexity. In reality, every state is purple – or at least has elements of red and blue scattered throughout. Even in states that one major party usually wins by a healthy margin, there is still typically a significant amount of support for the other major party.

For example, despite California being considered a very safe state for Democrats, Republican John McCain still won over 5 million votes in that state in the presidential election of 2008. That gave McCain almost 37% of California’s vote - not nearly enough to win, but still a significant amount of support. To call the state purely “blue”, despite being electorally accurate in today’s system, is misleading and fails to represent the fact that more than a third of voters in the state actually were “red”.

On the other hand, Republicans consistently win the state of Texas by a significant margin. Still, in the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama won over 3.5 million votes in that state, giving him over 43% of the vote. Painting the state simply as “red” fails to show that close to half the state supported the “blue” candidate.

In U.S. presidential elections, a 60-40% win in a state is considered nearly a landslide. And yet, we must recognize that even 40% of the vote, especially in populous states, can represent quite a large amount of support. The overly simplified red state/blue state paradigm enforced by the current Electoral College system fails to show that, far from displaying overwhelming party favoritism, even the states most heavily supportive of one party still have quite a large number of supporters of the other. In a nation plagued by a history of vicious division, the red/blue map tends to unnecessarily reinforce a perception of extreme polarization between different states even where it does not actually exist.

Allowing huge consequences to hinge on tiny margins in particular swing states can unnecessarily further exaggerate and escalate the sense of division in the country

Most of us remember the incredible debacle that was the aftermath of the 2000 U.S. presidential election between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Due to the nature of the Electoral College, the outcome of the election hinged on the fight over a relatively small number of ballots in particular parts of the swing state of Florida. That clash and the ensuing Supreme Court decision, Bush v. Gore, bitterly divided the country.And yet all of this polarization occurred despite the fact that Al Gore had been favored in the country at large by over 500,000 voters. What was, in reality, not quite as close an election was twisted by the current Electoral College system into the illusion of a “too close to call” battle, with very real consequences for the mood and tone of the country. Even if Gore had ended up winning Florida and the presidency, the battle that the Electoral College required would still have been an unnecessarily traumatic national event.

Such “artificial” close calls, where clear victories are transformed into vicious disputes in swing states, make up just one more of the commonly cited problems of the current Electoral College system.

The Challenge of Eliminating the Electoral College

The National Popular Vote Bill: A Third-Hand Solution

The bill takes advantage of the fact that, when our founders established the Electoral College in the United States Constitution, they also specifically gave each state the power to decide how to choose its own electors.

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution begins:

"Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors . . ."The Supreme Court, in a case called McPherson v. Blacker, reinforced this fact, declaring that:

“the State legislature's power to select the manner for appointing electors is plenary…”As mentioned, currently almost all states have decided to choose their electors through a winner-take-all state election, where the candidate receiving the most votes in the state receives all of that state’s electoral support. However, if it chooses, any state can change its law so as to allocate its presidential electors in another way. Not only is it Constitutional to do so, but throughout our history many states have chosen their electors in other ways. In fact, early in U.S. history, very few states chose their electors through winner-take-all elections. And, as alluded to earlier, even now two states, Maine and Nebraska, choose their electors in a manner other than winner-take-all. (Specifically, in both states, one elector is given to the candidate with the most votes in each of the state’s congressional districts, and then two additional electors are chosen based on the winner of the statewide vote.)

What this means is that, if it chooses, through its own laws, any state can decide to allocate its electors according to the winner of the total popular vote in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, rather than just the winner among its own voters. In other words, the third-hand solution is to leave the Electoral College intact, but simply have states opt to choose their electors based on a different criterion than they currently do – namely the outcome of the national popular vote.

The National Popular Vote Bill: An Assurance Contract

The National Popular Vote bill solves this problem by taking the form of an interstate agreement or compact. Each state is encouraged to enact identical legislation and that legislation specifies clearly that, even if passed, it will only actually go into effect when enacted by enough states to reach a certain threshold. That threshold is when the legislation is enacted by a group of states whose total electoral votes equal at least the 270 required for a majority in the Electoral College. At that point, the states within the compact will, amongst them, have enough electoral power to guarantee that the winner of the presidency will be the winner of the national popular vote. No state will be unilaterally giving up its power because the statewide election totals will have become moot for all states. The national popular vote will, in effect, determine the winner.

This mechanism is an example of what is known as an assurance contract – a contract in which each party to an agreement assures the others that they commit to going forward with a plan, but only if enough of the other parties also commit to make the plan viable. Assurance contracts are themselves a form of third-hand solution, transcending the dichotomy between sticking with a bad system because no party wants to risk unilateral change and having certain parties altruistically take that risk and possibly be unfairly punished for doing so. I also like to call such solutions “contingent commitments.” They are also very much related to the concept of a “trigger law,” a law that is clearly designed, but includes a mechanism by which it only goes into effect if a certain condition, or trigger, is met.

The Benefits of the National Popular Vote Bill

- The presidency will always go to the candidate that most Americans voted for, giving him or her a greater mandate upon taking office.

- All votes for President will be effectively made equal, regardless of what state the voter is in.

- Presidential candidates will have an incentive to focus their campaign resources on the voters and issues in all of the states and the District of Columbia, rather than only a few swing states.

- Voters in non-swing states – which make up by far the majority of states in the country – will be further incentivized to vote, possibly increasing voter turnout.

- We will eliminate the risk of purposely or even accidentally favoring particular interest groups that just happen to be more prominent in swing states

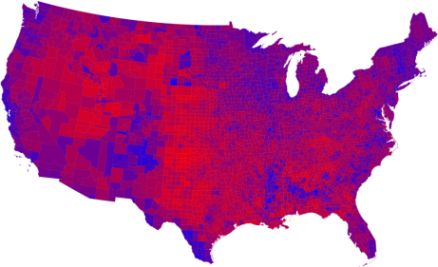

- The familiar red state/blue state map will be replaced with a more realistic map in which the country as a whole, and every state within it, is purple (or at least displays a much more integrated distribution of red and blue areas).

(Map showing 2008 presidential election popular vote winner by county)

Thus, presidential election campaigns and results will contribute to a more accurate national and regional self-image reflecting the diversity of political opinion that exists throughout the country and within every state.

- Presidential election results will more accurately reflect the fact that, as a whole, Americans have always clearly voted in greater numbers for a particular candidate. No longer will the country endure traumatic and divisive close-calls in particular swing states - such as the 2000 Florida debacle - that are unnecessarily and “artificially” manufactured by the Electoral College.

Criticism of the National Popular Vote Bill

First of all, even if this were true, there is a strong argument to be made that this is simply as it should be. Shouldn’t the areas with the most people receive proportionate attention from presidential campaigns?

Furthermore, most critics of the plan, who are states’ rights advocates, must admit that the NPV bill is itself a shining example of states’ rights. The states that enter into the compact are exercising their explicit Constitutional rights to decide how their presidential electors are chosen. If they wish to enter into a compact of this type, that is states’ rights at its finest.

But, on top of all this, we must acknowledge that, as it is, less populous states already receive almost no attention in presidential campaigns. Few, if any, low-population states are swing states, and therefore candidates have no more incentive currently to focus their campaigns on them than they do on any other non-swing state. At least with the National Popular Vote bill enacted, all candidates will have an incentive to win every vote they can in those less populated states, even if they know they are unlikely to win the most votes in any particular state. Under the plan, rural votes and urban votes in all areas of the country become equally valuable.

Widespread, Diverse Support for the National Popular Vote Movement

- A 2007 Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation-Harvard University poll showed 72% support nationwide for electing the President by “direct popular vote, instead of by the electoral college.” More specifically, direct election was supported by 78% of Democrats, 60% of Republicans and 73% of Independents.

- Support for the measure is bipartisan enough that it has been advocated and/or endorsed by many presidents and Congressional members of both major parties and Democratic and Republican leaders have come together to editorialize on its behalf.

- Perhaps even more impressive evidence of the measure’s diverse support is the fact that the advisory board of National Popular Vote, Inc., a non-profit which advocates for the National Popular Vote bill, includes respected Republican, Democrat and Independent ex-Congressmen.

- It has the support of many newspaper editorial boards throughout America.

- The measure is also supported by a variety of concerned organizations.

Progress of the NPV Movement

Of those 10, it has been enacted into law in 6 states – Hawaii, New Jersey, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts and Washington. These states possess 73 combined electoral votes or 27% of the 270 electoral votes needed to trigger the legislation into effect.

You can view the latest updates on the progress of the NPV bill around the country and in your state.

The Growing Public Attention to the NPV Movement

After the Massachusetts Legislature completed action on its National Popular Vote bill (H 4156) on July 27, 2010, sending it to the desk of Governor Deval Patrick for his signature, I noticed that the Drudge Report featured the news highlighted in red.

(Front page of DrudgeReport.com, July 28, 2010.

Red headline magnified)

That same day, I saw afternoon anchor Rick Sanchez on CNN say:

“Have you heard about this? There is a movement in this country to change the way we Americans pick the President of the United States. Have I got your attention?...This is an important story that we just put on our radar. We are going to be all over it. Expect follow-ups. And expect us to have another conversation about it tomorrow, a national conversation.”As the bill passes in more states, and the 270 electoral vote threshold is approached more and more closely, expect even more media coverage and public conversation on the issue.

How You Can Support the National Popular Vote Movement

Communicate and Catalyze Support for the Particular NPV Bill in Your State

- Start by checking the status of the bill in your state.

- If it’s already been enacted, you might want to contact your state representative, state senator and/or governor to let them know you appreciate it.

If it hasn’t yet been enacted in your state, contact your state representative, state senator and/or governor to urge them to vote for/support it. Encourage your family, friends and others in your state to do the same.

- There are a few helpful tools to aid you in voicing your support.

- NationalPopularVote.com’s Local Official Lookup, Sample Letter and Contact Form – Just enter your zip code, edit the sample pro-NPV letter to put it in your own words, complete the form and hit send to quickly voice your support for NPV to your appropriate state officials.

- FairVote’s Local Official Lookup, Sample Letter and Contact Form – Another option, similar to NationalPopularVote.com’s form, only with a somewhat more detailed sample letter that you can edit. Type in your zip code, edit the sample letter to your liking and click send. The letter will then go to your state representative, senator and governor expressing your support for passage of the National Popular Vote bill and encouraging them to take action.

- Another Sample Pro-NPV Letter from FairVote Electoral Reform Activist Neal Suidan – You can use this to guide the writing of your own letter, but be sure to use your own words.

- NationalPopularVote.com’s Local Official Lookup, Sample Letter and Contact Form – Just enter your zip code, edit the sample pro-NPV letter to put it in your own words, complete the form and hit send to quickly voice your support for NPV to your appropriate state officials.

- One other potential option, for more involved political activists, would be to promote a ballot initiative in your state – similar to the local one I coordinated for Instant Runoff Voting – to give the public itself the chance to pass the National Popular Vote measure into state law. If you are interested in doing this and need help, you might consider contacting the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center

Support the National NPV Movement

There are a few ways that you can support the National Popular Vote bill even outside of your own state.- Let your contacts in other states know to use those same tools listed above to check the status of the bill and contact their elected leaders in their own states.

- Donate to National Popular Vote, Inc.

- Look at the other recommendations under the “Take Action” tab on the top right of the header menu at http://www.nationalpopularvote.com

National Popular Vote: One Step in the Right Direction

As affirmed by the Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore, Americans currently do not have a Constitutional Right to Vote. The Constitution gives such a right only to electors. And, as mentioned, each state may appoint those electors "...in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct…” and “the State legislature's power to select the manner for appointing electors is plenary…”.

In other words, states may choose their electors in any fashion they wish. Residents of the states currently have a role in choosing electors only because their states’ legislatures have chosen to grant them that role. This situation leads to many potential problems with disenfranchisement and can only be remedied through a Constitutional “Right to Vote” amendment.

Furthermore, addressing issues such as non-majority winners and a lack of proportional representation in many of our elections at all levels will require different legal measures.

But the enactment and activation of a National Popular Vote bill would definitely be one more step toward a fairer U.S. election system.

More Resources Regarding National Popular Vote

-

National Popular Vote, Inc. - “National Popular Vote Inc. is a 501(c)(4) non profit corporation whose purpose is to study, analyze and educate the public regarding its proposal to provide for the nationwide popular election of the President of the United States.” Its website has a great deal of information, news and updates on the progress of NPV, along with tools to help advocate for it.

- FairVote’s “National Popular Vote Plan” page – Explains and links to information, articles, brochures and even a Powerpoint presentation regarding NPV.

- FairVote’s pro-NPV Video “Make Every State Purple” – A 4 minute video that touches on the problems with our current Electoral College system and how NPV can fix them.

- FairVote National Popular Vote Brochure (PDF) – Great for handing out or mailing

- FairVote’s National Popular Vote Plan Facts and FAQ Page

Books

- Every Vote Equal: A State-Based Plan for Electing the President by National Popular Vote - A very thorough look at the current presidential election system and how and why the National Popular Vote bill can improve it. Written by a number of electoral reform experts.